Demand for delusion

Being an investor, a dividend is something I rather enjoy. And yes, I do happen to be one, on occasion. When I have some money to spare and no idea what to spend it on that is, and then I don't exactly have a start up of my own that would require funding in the pipeline either. Any amount is a good amount to invest. Another thing I'm quite fond of is some growth and stability. Oh, and no excessive risk. That’s about it. I assume that most (long term) investors share the same view in principle. So, when I decide to buy a company's stocks I am willing to understand it all better. I seek signals, some information on what might suggest growth or decline in value, or the possible ROI to be achieved just from the dividend. I know no accurate information is available to me and I can only judge and interpret what the company is trying to sell. I had better be careful.

The company board is doing the actual job to deliver and to please me. They need to make sure the shareholders are going to hold onto their shares, not think of getting rid of them. It would be too dangerous for the company (stock) value to let that happen. So the managers also attempt to guess what the message should be in order to keep the stakeholders calm and convince them to stay loyal. This is where some managers clearly fail by always declaring growth, independently of the reality and feasibility of the strategy.

There is no such thing as a company able to grow forever. There is however huge space for growth at the startup phase, 10% CAGR might last for a decade although defending turnover and profits at a certain level of saturation is much more likely to happen. And I’d like to own shares of firms willing to (identify and) admit honestly when they hit this stage. Just to allow me to make conscious decisions, rather than leave me feeling surprised and disappointed. Common sense tells me it's not too difficult to check generally widely-available information. Even when the official communication coming from the business calms down, one should beware if:

- the industry is opposing (unstoppable) trends. Traditional retailers selling electronics are not going to grow. This is all going online. Unless they switch their business model and adjust or, even better, create solutions, nobody should believe in development. Gaining a market share in a shrinking value pool consumes a huge part of any profit.

- the industry is saturated, and the company is a big (but not the only) player (a leader or the second). Unless the business has unique, hard to copy products/services, a price war is about to happen (see “Third player syndrome and how to deal with it”). Profits will disappear.

- the business repeatedly fails to achieve the growth they declared. It’s only going to get worse in the future.

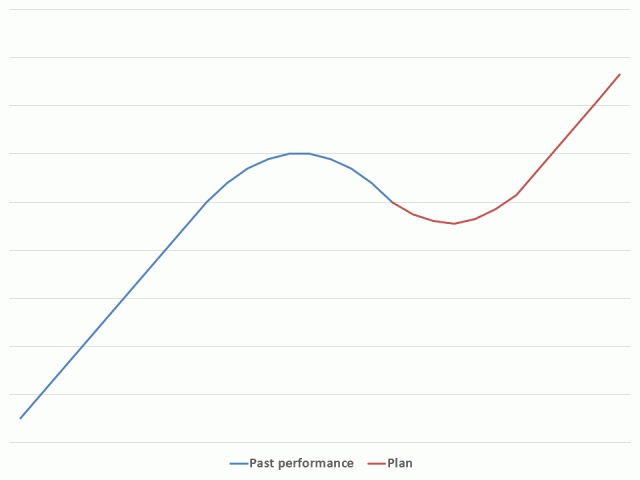

While the first two might be handled by decisive and effective CEOs (if they are given the opportunity to do so, see “Two year manager”), the last scenario might suggest that,for some reason, facing reality is not an option for the management, though definitely not sharing the not-so-optimistic forecasts actually is. Have you ever seen a trend reversal declaration without a planned revolution in the business commercial function (see Fig. 1)? It’s not going to happen.

There is nothing wrong with ambition. It might genuinely bring the business forward. But overambitious (unachievable) goals, resulting from unrealistic declarations to the shareholders do the opposite:

- The plan presented to shareholders naturally feeds the business budget.

- The budget is then translated into an overambitious compensation system. The employees easily identify it as wishful thinking and do not even attempt to deliver.

- After a month, there is both a sales and a profit gap, which need to be filled in over the next 11 months (targets become even more absurd).

- After a quarter, the shortfall in the plan seems to be the only growing quantity describing the business's performance. It’s clear that making up for this is not feasible, and the first hard decision needs to be made: sales or profit. Only one of them can be (still) achieved. Going for sales means discounting and this works in the short term as the opposition is likely to respond. The lag in response is the only real time of advantage. Then sales go down and the overall industry profit pool remains damaged for good. Going for profit means cutting costs, marketing being the first choice, then recruitment, freezing pay rises, training programmes.

- At the end of the year it’s a business with broken profitability, or broken brands and people. Underperformance is a fact, investors feel deceived (some of them will never buy this company's shares again) and the stock value goes down – most likely much more than the actual results would suggest (emotions become a significant decision factor). It’s not going to grow until trust can be restored.

Declaring a realistic (but not so ambitious) plan instead might lead to some stock value discounting before anything happens, but there is a huge difference here – as the future is still unknown, good results are considered to be an option. The risk remains just that - a risk, it’s not as tangible as realized underperformance. So the decline in the stock value is going to be much more moderate compared to when failure becomes a fact. Investors are not going to feel deceived and might well be willing to invest more in the future. But most importantly – the pressure to make short term decisions (with long-term destructive consequences) is likely to be avoided. No business wishing to stay in the market for long can afford to cut marketing expenditure or convince their best employees to quit. A realistic plan assumes the right investment level to keep the business healthy.

So, why do some managers keep repeating the same errors and overestimate the business growth potential? I guess they want to maintain high stock prices for a bit longer, to prove they are ambitious, to justify their high salary, or to avoid being sacked for excessive conservatism. Most probably all of these apply to an extent. And there are investors who are willing to punish the managers for not coming up with irrational plans. Majority investors directly, by appointing new managers, small investors indirectly, by selling out shares and dumping their prices. The demand for growth is so huge that only growth plans are acceptable, even if this is just a delusion.

For me, a small investor, it’s valuable to identify these vicious circles, pathological business – shareholder relationships, where the majority of shareholders ask to be lied to, and the appointed CEOs make promises they cannot keep. These obsolete blue chips are the businesses which actually pose the highest risk, with no chance of earning any equity premium. As far as investment goes, they are to be avoided more than any other business.

Image source: broken dreams, broken heart, broken relationship, broken key by Andreas Wieser